Editor’s note: This is a repost of a TechCrunch article written by Christine Magee and Mark Lennon.

Winter is coming in South America, but for investors and entrepreneurs things are starting to heat up across the continent.

New tech communities are sprouting up in South America to serve the 200M+ population that is increasingly reliant on internet and mobile technology.

In June the accelerator program Start-Up Chile announced Generation Ten, its latest batch of nearly 100 startups set to arrive in Santiago this summer. Fully funded and supported by the Chilean government, Start-Up Chile is the first of many state-sponsored seed funds to emerge in South America over the last few years.

The success of the program has spawned complementary programs around the region – Start-Up Peru in Lima, Startup BA and Incubar of Argentina, and Colombia’s iNNpulsa, among many others. All are government-backed initiatives designed to catalyze the creation of local startup communities.

By offering grant money with no strings attached, the Start-Up Chile program has been successful in attracting entrepreneurs to the country – but less successful in keeping them.

After completing the 6 month program, nearly 80 percent of entrepreneurs left Chile, 34 percent of them for the United States, according to a recent survey shared with us. Batch Ten is the first group in which Chilean entrepreneurs are representing the plurality of participants.

Despite Start-Up Chile’s success in importing talent, the Chilean ecosystem — and that of South America as whole — lacks the resources to keep young companies alive.

The Series A Crunch

“Everyone uses incubators as ATMs,” says Chilean entrepreneur and investor Tadashi Takaoka of Magical Startups. “It’s the place you get money, but the process isn’t that strong and the results aren’t that good.”

Takaoka points out that the emphasis on education and mentorship in these incubator programs is initially very helpful, but upon completion of the program, many entrepreneurs are unable to scale their businesses.

“You have Start-Up Chile, then venture capital funds, and nothing in between,” says Chilean investor Cristobal Silva of Fen Ventures. “We have a lot of companies in these [incubator] programs, but the problem is that these programs are 6 months, 8 months, a year, and then what?”

For Silva and many other Latin American investors, the problem lies in trying to bridge the gap between seed-funded entrepreneurs and companies worth a Series A round. Follow-on venture investments have been rare across South America thus far, with the exception of Brazil.

As a result, early stage companies are calling institutional investors to finance their first steps –an unlikely prospect in the traditionally risk-averse investment culture of Latin America. “You have a company with $100k, a product and some traction, and they work for one or two years. Then they have to survive until they get to a $10 million dollar valuation– how do you do that?” asks Silva.

An obvious solution to this problem is to enlist high-net-worth individuals to invest in the startup community. But generations of economic uncertainty have tempered the appetite for risk.

“My reality is completely different from the older generations who have been working for 40 years at the same company,” says Silva. Many successful Chilean entrepreneurs from previous generations built their businesses over multiple decades without the assistance of venture capital, and are not accustomed to the fast-paced and capital-intensive startup culture.

Adding to the reticence of most high net worth investors is the high percentage of failure in the startup world. “There is a cultural thing with failure here,” Silva concedes.

Entrepreneurs that have made fortunes abroad are also reluctant to return. “Most of the Chilean entrepreneurs I know are living in the States right now. I could probably find more of those guys in San Francisco than in Santiago, to be honest.”

Filling the gap between seed funds and institutional money is not only a question of more angel investors or more money. Large corporate investors like Intel Capital have shown a willingness to invest capital in the region, but have done little to further develop the investment pipeline because they don’t offer the guidance and services VCs provide to young companies in Silicon Valley, according to investors and entrepreneurs in the region.

But some savvy ex-entrepreneurs like Nicolas Szekasy see opportunity where others see constraints, returning home after successful exits to become investors. After taking MercadoLibre public in 1997, CFO Szekasy co-founded one of Latin America’s largest venture capital firms, Kaszek Ventures, along with MercadoLibre co-founder Hernan Kazah. “We bring significant operational experience. We think this is extremely helpful for us as investors”, says Szekasy. “It provides credibility to entrepreneurs- we’ve been there, where they are.”

In Uruguay, Pablo Brenner of Prosperitas Capital has followed suit. After taking his company Alvarion public in 2000, Brenner returned to Montevideo to start the country’s first VC fund. “You have to understand how an entrepreneur thinks, and understand that things are not always great at the beginning,” says Brenner. “You see entrepreneurs trying to restart the industry in their countries who are having more success than the financial guys. It’s not a business for finance guys here.”

Rise Of The Copycats

The risk-averse culture could be one way to explain the large portion of funded Latin American companies that appear to be regional clones of successful U.S. business models.

The success of these and other so-called “copycats” have led Latin American investors to assume that investments in clone companies are less risky. “I find investing in copycats kind of boring,” says Brenner, “but it is a successful venture capital model– you see that you have OpenTable successful in the U.S., so then you start Restorando in Latin America.”

But Restorando investor and board member Szekasy disagrees. “[Copycat] is a word that comes across a lot, but I’m not sure that’s the word I would use– I don’t think these models, even in the U.S., were huge innovations. They were just adaptations using the technology.” Szekasy argues that even if these “copycat” companies are similar to their U.S. counterparts initially, they have to adapt and adjust along the way to serve the local market and ultimately end up with very different business models.

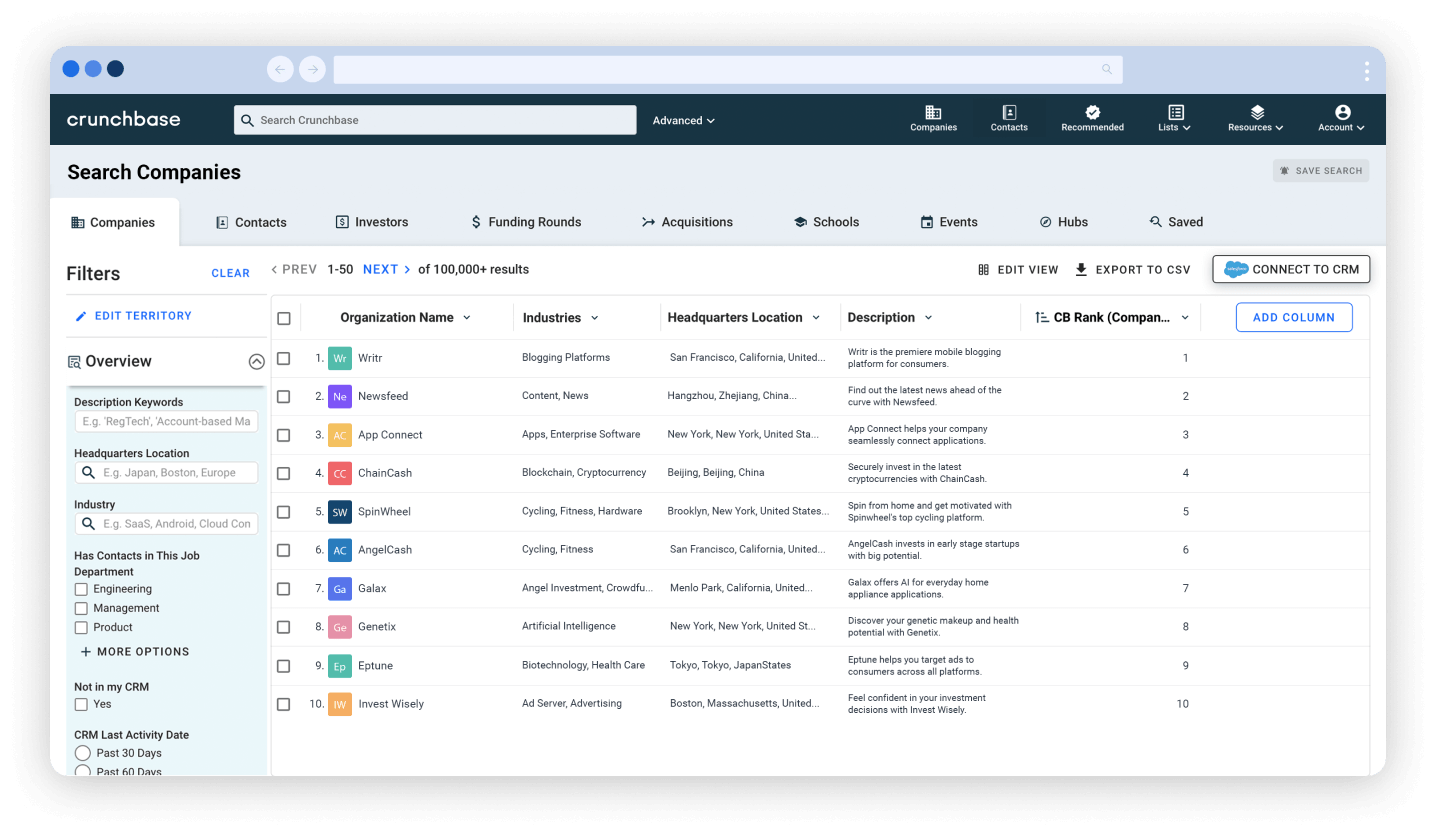

Copycat or not, the lack of angel investors and early stage capital is causing entrepreneurs to leave these developing Latin American startup hubs once they’ve established a business model. According to CrunchBase data, Brazil is the dominant regional leader in number of rounds and investment totals, and appears to be drawing a lot of founders from neighboring countries with less-developed ecosystems.

Szekasy has noticed this as well. “Even if founding teams are based elsewhere, very early on they go to Brazil and continue expanding from there with the objective of becoming a regional leader,” he says. The instability and size of many national economies in South America has forced many startups to relocate in order to scale their businesses.

Why Brazil? Because “you can build a billion dollar business in Brazil,” whereas “in any other country in Latin America that is not really possible,” says Szekasy.

But this could be changing. “I think Latin America could make good sense,” says Silva. While the costs of living and running a business are rising in the U.S. and Europe, labor and working space are still relatively cheap in up-and-coming South American startup hubs. And state governments in Chile, Colombia, Peru, and Argentina are forming new trade agreements that eliminate taxes and restrictions across borders to facilitate international business. “I think in a couple of years it’s going to be an interesting market,” Silva concludes, “it will just take some time for us to get there.”